Barriers To Entry

Big Tech doesn’t need power on paper: it needs physical power at the right place, at the right time.

Traveling through Europe, you might come across seemingly countless castles, some built for beauty, some for defense, and some for both. As seen in the picture below, many castles were built with massive barriers to entry, hopefully to keep uninvited guests out. But once those barriers get thrown up, that space inside becomes constrained, and it can quickly become a zero-sum real estate game. To build a new structure inside the walls, you might have to tear something else down.

It’s a similar problem for the grid when government regulations effectively raise barriers to entry and make it more difficult to add reliable power stations to the grid. What happens to that ‘real estate’ within the castle walls?

One of the biggest drivers of growing electricity demand today is the power consumed by data centers. Data centers are vast banks of computers that can form both digital libraries and provide computing power. By using centralized computing and storage, a business can get better performance, lower costs, better backup, and better cooling systems. It operates much the same as a physical library: you can have a deeper selection of books in a centralized location than if you tried to duplicate that selection of books in each and every household.

If you’re curious of where some of those data centers are located, here’s a link to a map. This doesn’t mean it’s an exclusive, comprehensive list, but it gives you an idea.

In the US, the state of Virginia became the Mecca for data centers, hosting facilities for some of the biggest names in tech, such as Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and giants in the financial industry including Visa, Bank Of America, and Capital One, along with many other businesses.

Here is a map of ~ 85 data centers clustered in a part of Northern Virginia. Notice that the scale is just 1 km.

This mass concentration in Virginia was due in part to deliberate state government strategy years ago exempting data centers from sales and use taxes on the purchase equipment. Virginia offers a relative low risk environment, isolated from most major earthquakes, tornadoes, and hurricanes. The state has close access to Washington DC and Virginia offers a superb fiber optics network including critical transatlantic connections.

But data centers also need lots of relatively cheap power. According to the IEA, 40% of a data center’s electricity is used for computing, 40% for cooling, and the rest for IT and other uses.

To supply power, Virginia’s electricity production is dominated by natural gas (54%) and nuclear (31%). According to Dominion Energy (a major provider in the area), it is able to offer data centers in Northern Virginia electricity rates ~30% below the national average. And when data centers consume as much electricity as a small city, price matters.

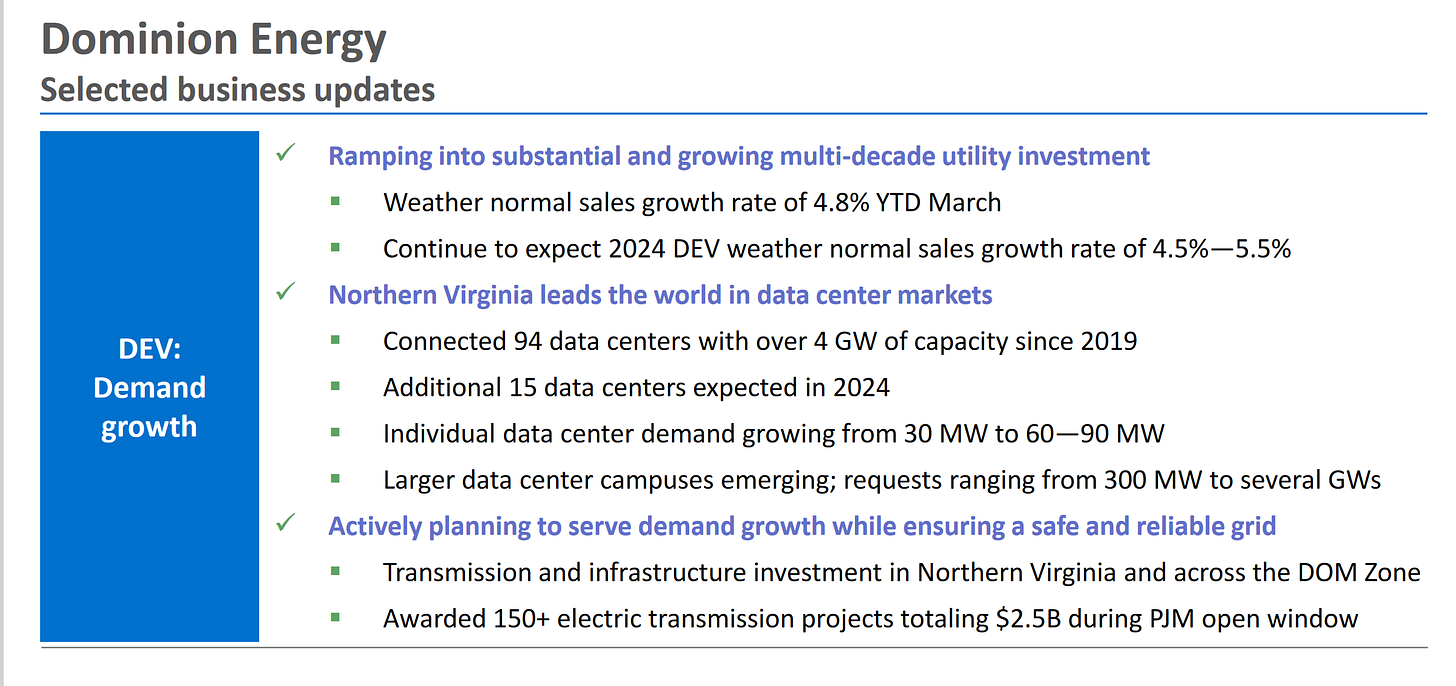

According to Dominion, the average data center in Northern Virginia has more than doubled to 60-90MW. The largest planned data centers are requesting 300MW to well over 1 GW+ of power connections. Here’s a screenshot from Dominion’s 2024 Q1 earnings presentation, highlighting data center growth.

But Virginia isn’t alone: demand is going up globally. According to a 2024 report by the IEA, cryptocurrency, AI, and data centers consumed around 460TWhr of electricity in 2022. For reference, that’s roughly Germany’s grid. While we should always take projections with a grain of salt, if the IEA’s forecasts are correct, that electricity demand could hit 800+ TWhr by 2026.

The Big Question: How to Power Data Centers and Big Tech?

First, as most readers know, there is a big difference between the paper grid and the physical grid. On paper, you can easily power a data center with solar. You just buy ‘solar’ credits from the utility. The utility acts as a middleman and guarantees you get a certain amount of power and might contract a solar farm in your name. When the sun isn’t shining, the utility can still provide electricity from natural gas, coal, etc, but you still have the credits for the solar farm or you can buy credits from someone else. Basically, you can pay a solar penance for the perceived sin of fossil fuel use. With the penance paid, you can self-proclaim that you’re environmentally righteous.

That paper grid hops, skips, and jumps right over a lot of hard-to-solve physical problems - like how to store and transmit real electricity over distance and time. Those paper credits don’t have to necessarily be generated when or where they are needed (depending on the type).

For example, when Apple announced it was powered with 100% renewable energy, it had a major footnote that many people missed. To make that claim, Apple relies on ‘virtual’ power agreements. Here’s a page from Apple’s 2024 ESG report:

Virtual renewable power is a lot like having virtual lifeboats: it’s a way to virtue signal, but virtual lifeboats won’t keep you dry when and where you need physical lifeboats.

But what about Solar + Batteries?

Recently, the IEA published a report claiming solar + batteries will soon be competitive with natural gas plants. That claim gained re-posts on X, and could give one the impression that solar plus batteries could take the place of coal or natural gas power plants. But….the IEA’s claim is based on critical assumptions:

It calculates the cost using only 4 hours worth of battery storage

Both battery and solar prices need to fall another ~35-40% by 2030.

Here’s the IEA’s chart, with only slight modifications in red.

Of course, those 4 hours of battery backup might not last a single night, particularly if it was cloudy the day before. And four hours of batteries don’t cut it for 24/7, 365 days a year power when you consider how seasonal solar is.

The EPA’s New Rules

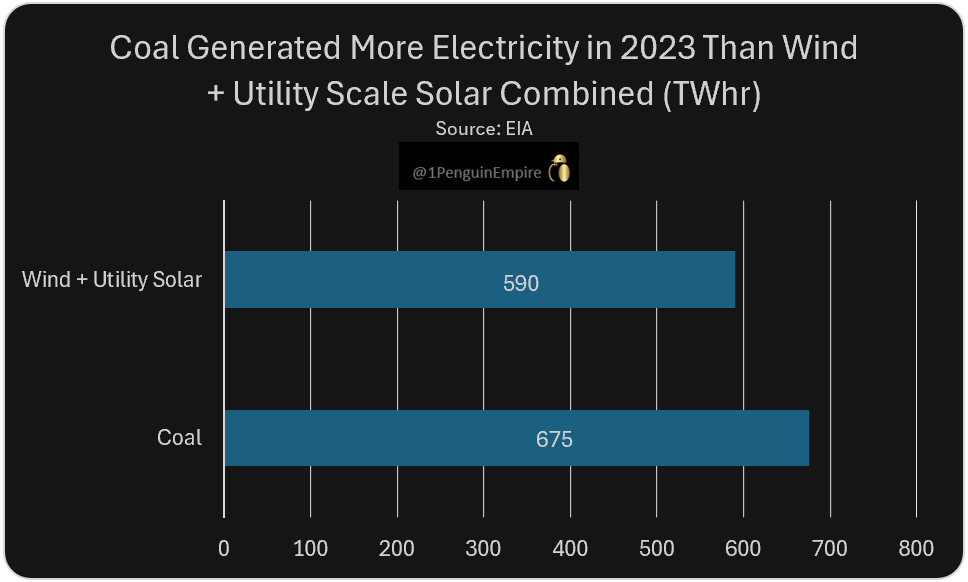

Coal, despite being hated, offers something wind and solar cannot: steady state power 24/7 regardless of if the wind is blowing or if the sun is shining. And despite all the years of subsidies and mandates pushing for renewables, coal is still bigger than wind and utility solar COMBINED. As

recently pointed out, in 2023 in the US, coal generated more electricity (675TWh) than wind (425TWh) and utility solar (165TWh).Needless to say, coal supplies a massive chunk of the US’s grid and offers seasonal and daily reliability that wind and solar can’t offer.

Earlier this year, the US Environmental Protection Agency rolled out its carbon capture rules for power plants. Basically, if you want to keep existing coal plants, you have to install carbon capture by 2032. But carbon capture for coal is astronomically expensive, costing multiple times the cost of a new gas power plant. This means there’s a real possibility that a large portion of America’s reliable grid will either shut down, switch fuels, or have to spend billions in upgrades (which, incidentally, will be subsidized under the Inflation Reduction Act).

What About Small Modular Reactors Or Natural Gas?

While the idea of small modular reactors (SMRs) is very exciting, they’re a long way from commercial viability in the US. NuScale boasts the only approved SMR reactor design. Back in 2015, the Utah Associated Municipal Power Systems (UAMPS) announced it was joining NuScale to develop what was supposed to be the US’s first new SMR power plant. Around that time, NuScale reportedly estimated it would cost about $5million per MW to build it. For an almost ‘fuel free’ power plant, it was an appealing idea. But, as is the way with novel projects, costs spiraled up. By the time UAMPS withdrew from the project in late 2023, costs estimates rose 4x to approx $20 million per MW. Net of government support, it was to cost around $11 million per MW.

In theory, SMR costs go down as production ramps up. But, NuScale’s first project was slated to be more expensive per MW than a large scale nuclear plant: The Vogtle Nuclear Power expansion project in Georgia came in at around ~ $ 14.4 million per MW.

While existing gas plants are not currently the target of the EPA’s new rules, new plants that operate more than 40% of the time will have to install carbon capture or burn hydrogen. Adding Carbon Capture to a gas plant will, according to the EIA, more than double the cost of both maintenance and construction. For instance, a new ~418MW combined cycle gas plant (single shaft) without carbon capture might cost around $1.3 million per MW installed. If we add carbon capture, the costs rise to ~ $3 million per MW.

The Talen Deal

So what would you do if you were a power plant owner facing this set of problems?

If the EPA’s carbon rules are allowed to stand, it will likely become very difficult to build new cheap reliable generating capacity to support the data center/AI tech boom. This complicates an already fragile grid that is inundated with periodic floods of renewables, rapidly followed by renewable droughts, leaving steady-state plants with boom and bust revenue streams.

In March of this year, Talen Energy announced it was selling its data center to Amazon. Talen also happens to own a nearby ~2.5 GW nuclear power plant. As part of the deal, Amazon agreed to purchase up to 960 MW of power from Talen’s nuclear power plant, for a fixed rate for 10 years, then at above market pricing.

While this is celebrated as a signal that big tech is getting behind nuclear, one should also pause to consider what this could mean when combined with barriers to entry raised by the EPA’s rules, and the heavy subsidies for renewables. The Talen deal effectively removes up to 1 GW of reliable capacity from the public market. Granted, it could also be argued that this deal will help keep the entire plant from closing by guaranteeing steady revenue in a market that is increasingly pushed towards intermittent and seasonal renewables.

Taking 1 GW of reliable power offline isn’t a problem if we could build and have steady revenue streams for cheap reliable plants. However, once those barriers to cheap power plants are set up… independent power plants are not necessarily obligated to sell power to the grid. Surviving reliable power plants may be incentivized to (effectively) exit the public grid and instead sell a portion or all of their power directly to data centers or other large customers.

In closing, with the EPA’s rule and the general push towards intermittent renewables, this could effectively help tilt the market towards a zero-sum game where big tech wins, and grid stability loses. But can we expect Big Tech to do any different if that is the way the rules of the game are set up? Is it right to hate the player, or is it past time to change the rules of the game and to tear down barriers to entry?

As always, thanks for reading.

I took a back of the envelope crack on what it would take to power a 300MW data center with solar and batteries. All the most positive assumptions. The facility would cover 25 square miles and cost $3.8 billion. Of course there would still likely be some days when you’d need gas backup.

Excellent analysis of the Talen/Amazon deal.