The Dieselgate Scandal

If the West trades all of its gasoline powered cars for EVs, what are we going to do with all of that 'leftover' gasoline? Let's look at Europe's Dieselgate Scandal for clues.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often does rhyme” - Mark Twain.

Today, we’re told that if we adopt EVs, it’ll substantially reduce oil demand. In fact, that assumption is baked into the cake behind the claims that EVs reduces our carbon footprint. Yes, manufacturing an EV ‘emits’ a lot more carbon than manufacturing an internal combustion car because batteries requires so many specialized metals. However, so the argument goes, an EV will make up for that by displacing gasoline demand over the life of the vehicle.

But it’s not that simple. Reality has a way of upsetting even the most carefully laid out ambitions of central planners. If we look back into the EU’s recent history, we can see a real world test of what happens when the political class tries really hard to reduce gasoline demand.

In the late 1990s, European politicians flew back from the Kyoto Accords in Japan, determined to take massive steps in reducing CO2 emissions from vehicles. The idea sounded so simple: mandate and incentivize cars to become more fuel efficient by switching from gasoline to diesel. Diesels are more efficient, and this efficiency -theory- would reduce CO2 emissions.

And so the bureaucrats and politicians got busy doing what they think they do best: fashioning an industry after their own image. The EU implemented regulations in 1998 targeting CO2 ‘standards’ of 140g/km, combined with various tax incentives designed to reshape Europe’s car manufacturing and to ‘encourage’ consumers to make the ‘correct’ choices.

Does any of this sound familiar? Hummm…….

Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with diesel. Diesel is a wonderful fuel that is essential for construction, farming, mining, railroads, shipping, and trucking. It is a fuel traditionally used mainly in heavy machinery because of the fuel efficiency, energy density, engine power, and torque. But the EU’s goal was to displace gasoline consumption by passenger cars with something marketed as more ‘environmentally’ friendly.

And the EU’s policies had a major impact. In the early 1990s, diesel cars made up approximately 10-12% of Europe’s car fleet. But that share grew nearly 4x by 2017, with diesel cars making up over 40%+ of cars on the road.

This love affair with diesels garnered some glamour in the press. In late 2008, NBC news reported that the

Green Car Journal named Volkswagen's 2009 Jetta TDI as the "Green Car of the Year"…"I think it signals that clean diesel has arrived," said Ron Cogan, the magazine's editor and publisher.

And the next year, an Audi diesel took home the Green Car of 2010 award.

But soon things fell apart in the mid 2010s in what is now known as Dieselgate. While diesel cars were predominately a European event, VW sold some in the US. And after testing, researchers discovered massive discrepancies between the emissions test results and VW diesel cars actual performance on the road. According to the EPA, “These vehicles emit up to 40 times more pollution than emissions standards allow.” As the scandal began to unravel, it was discovered that VW installed software to in essence ‘fake’ or ‘manipulate’ emission tests results on approximately 11 million vehicles.

With VW in the hot seat, EU authorities began to look closely at other manufactures, with multiple companies charged by prosecutors, investigated, or faced civil suits over allegedly manipulating emissions results. By 2020, Reuters reported that the combined fines, fees, and buybacks resulting from Dieselgate cost VW approximately €31.3 Billion.

Meanwhile, researchers began to question the premise that diesel vehicles actually reduced CO2 emissions over the lifetime while reportedly increasing pollution in European cities. While the scandal dampened the enthusiasm for ‘green’ diesel cars, Europe’s elites fell in love with the next big thing- EVs.

Is any of this a surprise? When governments quickly shift CO2 ‘standards’ to meet political targets, it’s easy to see how some businesses might just pretend to go along with the hype. This isn’t a criticism of diesel: it’s a criticism of the idea that we can program an industry as if it is a computer game.

So what happened with gasoline demand under Dieselgate?

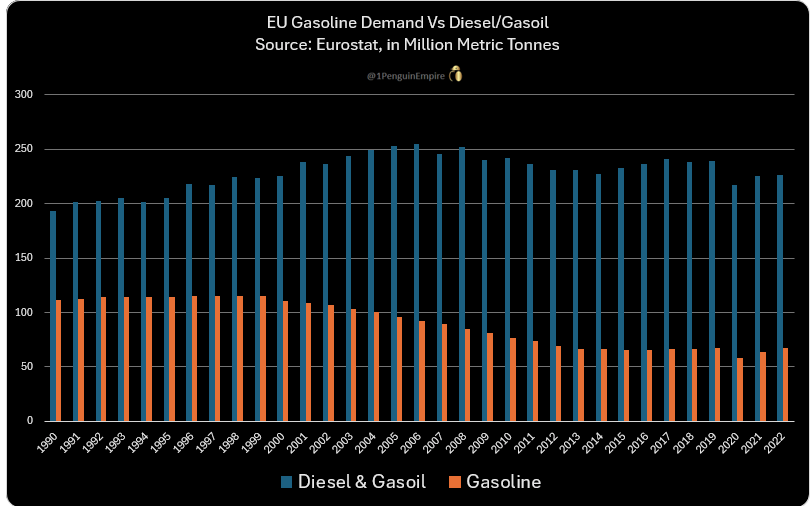

It might not be a surprise, but domestic gasoline consumption declined. And the EU’s domestic diesel/gasoil demand initially rose, partially offset by the simultaneous decline for heating oil/ other products made from gasoil, a very close relative of diesel.

And if we were to stop the story here, it might look like the EU achieved its goal.

But… there’s more.

Here’s something most politicians seem to miss: Diesel doesn’t just show up at the pumps - it has to be refined. And there’s a catch: an oil refinery can’t turn all of a barrel of crude into 1 barrel of diesel. There’s only so much diesel a refiner can make.

Refining 101

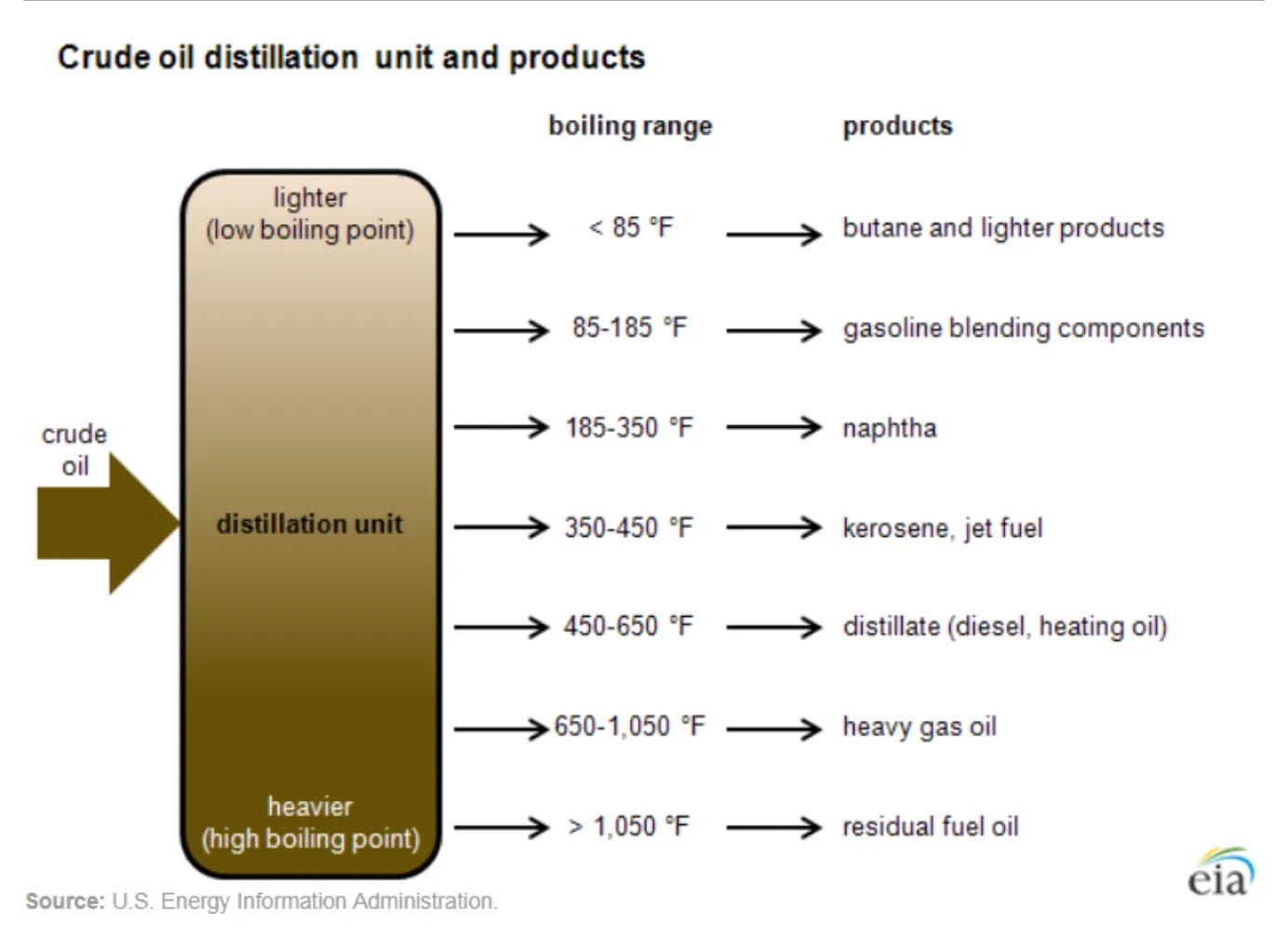

It all starts with crude oil. Crude oil is a bit like a trail mix. That tasty snack comes as a -well- mix of different products: pretzels, chocolates, nuts, and dried fruits. In much the same way, each barrel of crude is a mix of various hydrocarbon molecules, ranging from shorter-chain, lighter molecule to longer-chain, heavier molecules.

Using the different weights to their advantage, refineries sort the crude molecules using heat since the lighter molecules boil at lower temperatures.

Generally, a finished fuel - such as gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel - is made from a certain range of hydrocarbon ‘ingredients’ which are sorted by weight. Gasoline tends to be made from lighter hydrocarbon ingredients. Jet fuel and diesel tend to be made from medium weight hydrocarbons and there’s some overlap in the product types by weight, particularly with jet fuel and diesel.

But it’s not just molecule weight that a refiner has to worry about. There’s also the ratio of carbon to hydrogen. The lightest hydrocarbons- natural gas- have 4 hydrogen atoms and 1 carbon atom. But as we work our way up in weight - going from gases to liquids - the heavier molecules have longer carbon ‘backbones.’ This changes the ratio of carbon to hydrogen in the molecules, impacting the molecules features and performance.

Now complex and expensive refineries can add another step after ‘distillation’ and ‘crack’ the long chain molecules to make them lighter. But they may also have to either remove carbon and/or inject hydrogen to get the correct ratios, depending on the desired end products.

A refinery’s complexity can be measured on a scale of 1 to 20, known as the Nelson Complexity Index, with 1 tending to be the cheapest and simplest and a 20 tends to be the most complex and expensive.

Crude oil is also used for petrochemicals. Currently, most refiners turn a small amount of oil into petrochemical feedstocks. However, Saudi Aramco is trying to break that trend and is reportedly researching a Crude-To-Chemicals process, with the goal of turning 70-80% of a barrel of crude into petrochemical outputs. We’ll have to wait and see if it happens and if so, at what price.

There’s also a matter of crude oil quality. Not all crude types are the same and they vary by average weight (API gravity) and sulfur content. A region’s refineries tend to have been built around a certain range of imports or locally produced crude. And different geographical regions can produce different crudes. (The S&P provides an interactive Platt’s Periodic Table for global crude grades here and a guide for both North and South American grades here.)

When you combined the various crude options, the refining, ‘cracking’, and blending of products, (plus the treatment to remove sulfur, etc), refiners have some flexibility in output, but only to a certain point.

The EU’s Massive Fuel Imbalance

Let’s turn back to the EU’s Dieselgate to understand why it created such a massive supply/demand imbalance. While the EU imports the vast majority of it’s unrefined crude oil, the EU still has a major refining industry that produces most of the EU’s finished products.

Let’s go back to 1990. In that year, customers demanded a mix of 1.7 barrels of diesel/gasoil for every 1 barrel of gasoline. At that time, the market was nearly balanced. EU refiners produced a mix of 1.6 barrels of diesel/ gasoil for every 1 barrel of gasoline refined, with a small amount of imports and exports to make up the difference.

As the EU’s policies pushed down demand for gasoline, refiners could only do so much. In fact, by the 2020s, refiners only produced a mix of 2.2 to 2.4 barrels of diesel/gasoil for each 1 barrel of gasoline produced. At that same time, the EU needed a mix of 3.3 to 3.7 barrels of diesel/gasoil for each barrel of gasoline.

This left the EU’s refiners with a problem. If they wanted to keep up with diesel demand, they would produce a lot of unwanted gasoline as a ‘byproduct.’

In 1990, the EU refined ~120 million metric tonnes of gasoline, slightly more than domestic demand. But by 2022, the EU churned out ~100 million metric tonnes of gasoline from crude. By this time, diesel and biofuels had displaced a large portion of gasoline demand, resulting in a large amount of ‘unwanted’ gasoline. To make up the difference, the EU exports almost 50% of the gasoline it refines.

The EU’s real world experiment showed that simply displacing gasoline demand did NOT result in a proportionate reduction in gasoline produced. Instead, the shift from gasoline resulted in an artificial imbalance of refined products, leading the EU to import more diesel and jet fuel while vastly increasing gasoline exports. Ironically, the EU’s push to reduce domestic gasoline demand resulted in supplying other parts of the world with even more gasoline to use.

In the late 1800s before we had cars, we wanted kerosene to fuel lamps to illuminate the night. Kerosene is from the middle part of the barrel and since gasoline is the lighter part of the barrel, early refiners didn’t know what to do with gasoline. So, as much as it sounds surprising today, we used to throw gasoline away. Fast forward to the late 1990s and 2000s in the EU, and what happened?

History didn’t repeat itself but it surely did rhyme.

As always, thanks for reading!

Wonderful piece! Thanks. At the end of the day it seems to me that the political elites are vastly better at virtue signalling than at doing anything with real, net, global impact.

Heard a truthful one-liner yesterday about EVs:

People who buy an EV should also buy a dog, so that when they run out of power, they'll have someone to walk home with them.